“After (Maury) Wills successfully converted in the minor leagues from a right-handed hitter to a switch-hitter, it became common to try to convince young players who could run to switch hit. This was the worst idea in the history of coaching. It destroyed dozens of careers.”

— The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, 2001

Switch-hitting is a good idea in theory: Nearly all batters hit better when they face an opposite-handed pitcher, a phenomenon known as the “platoon advantage”. A switch-hitter always bats from the opposite side of the pitcher’s handedness, so he’ll always have this advantage. The glaring downside is that, for a naturally right-handed hitter, a majority of his at bats will be from his unnatural (and presumably weaker) left side.

At first glance, Gift Ngoepe seems to be a perfect example of switch-hitting gone awry.

Now 27, the Pittsburgh Pirates turned the speedy1 naturally right-handed shortstop — who became Africa’s first big leaguer when he made his MLB debut in April — into a switch-hitter after signing him to a minor league contract back in 2008, according to the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.

What followed was years of struggles at the plate. In fact, Ngoepe (en-GO-peh) struggled so much that in 2015 — his seventh season in the minors — he chose to abandon switch-hitting and bat right-handed full-time.

“I was struggling left-handed,” the South African player told the Tribune-Review. “I was struggling right-handed, too, but I knew batting righty I could make adjustments quicker and improve a lot faster.”2

In this article, I’m going to look at Ngoepe’s minor league numbers and try to figure out if the Pirates made a mistake by turning him into a switch-hitter at the start of his professional career. Hopefully, we’ll learn something about switch-hitting in general along the way.

Minor League Career

Ngoepe got called-up to the bigs thanks to his outstanding defense at shortstop3, which helped him slowly climb the minor league ladder, as the timeline below shows.

| '09 | '10 | '11 | '12 | '13-'15 | '16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rk | A- | A | A+ | AA | AAA |

AAA is the highest level of the minors, followed by AA, A+, A, A- and Rookie (Rk). To learn more about each level, read this piece from The Hardball Times.

*In years where Ngoepe played at multiple levels, the level at which he had the most plate appearances is shown.

In contrast, his bat has been a glaring weakness at all levels (and continues to be — Ngoepe was sent back down to AAA in May).

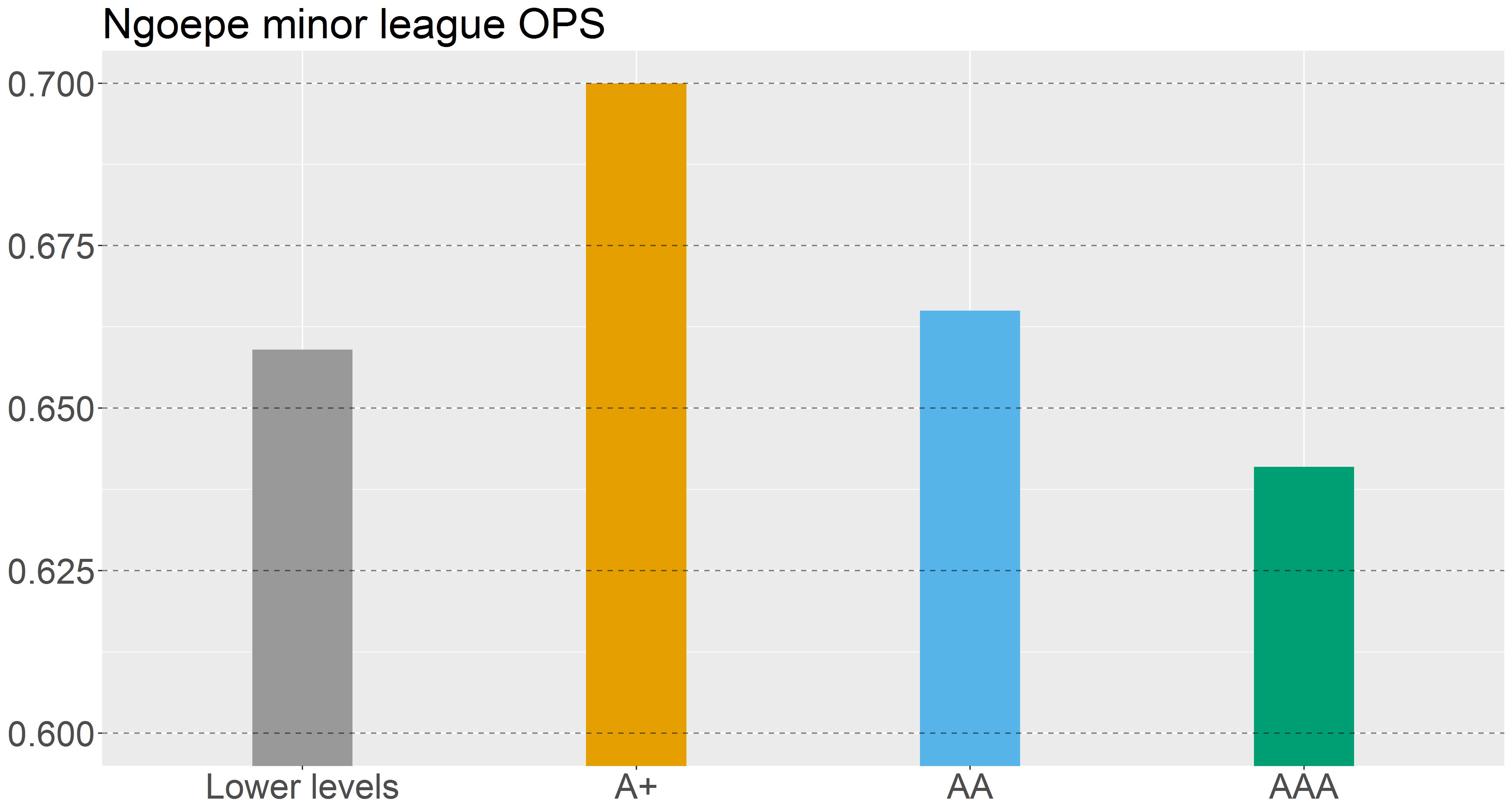

The graph and table below show Ngoepe’s minor league numbers from 2009-16. “Lower levels” refers to Rookie ball, A- and A.

Source: All stats in this article are from Baseball Reference unless otherwise noted.

Here’s a more detailed breakdown of those numbers:

| Level | PA | OPS | OBP | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rk, A-, A | 570 | .659 | .330 | .329 |

| A+ | 666 | .700 | .348 | .353 |

| AA | 1038 | .665 | .314 | .351 |

| AAA | 444 | .641 | .293 | .349 |

| ♦ Career | 2718 | .669 | .322 | .346 |

PA → plate appearances; OBP → on-base pct.; SLG → slugging pct.; OPS → on-base plus slugging (numbers may not add up exactly due to rounding)

To learn more about these stats, visit Baseball Reference’s statistics page.

Even without looking at Ngoepe’s platoon splits, my first impression is that a switch-hitter with such poor overall numbers was obviously not helped by switch-hitting. A minor leaguer with these stats would benefit from batting and practicing full-time from his natural side.

Because batters face more right-handed pitchers than left-handed pitchers, the Pirates decision in 2008 meant Ngoepe — a raw, developing hitter — spent the majority of his first five seasons batting from his unnatural left-side.

(For the rest of this article, we’ll only look at Ngoepe’s 2009-14, the seasons he spent as a switch-hitter.)

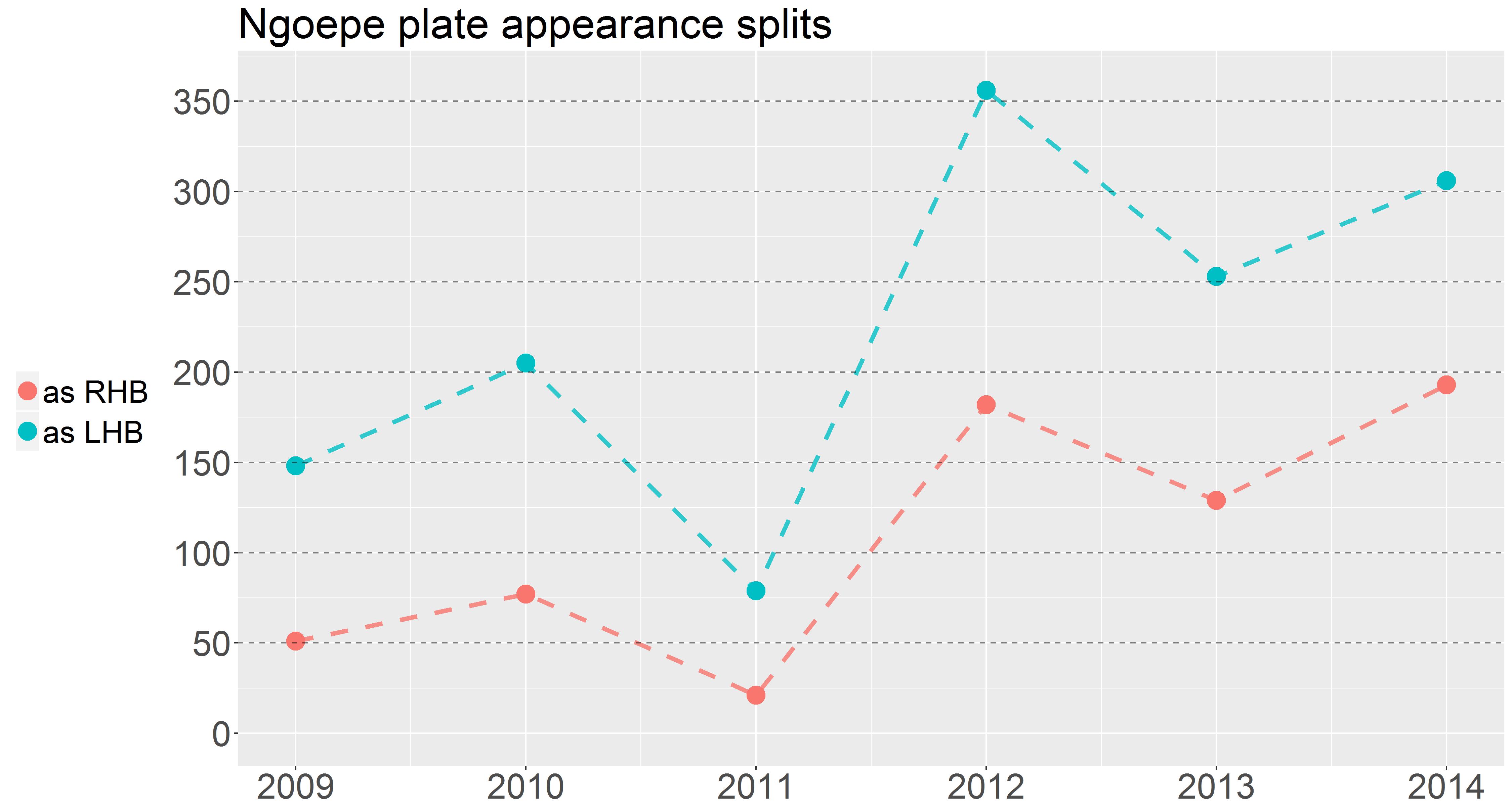

Below is a breakdown of his total plate appearances.

| Split | PA | Percent of PA |

|---|---|---|

| as RHB | 653 | 33% |

| as LHB | 1347 | 67 |

| ♦ Total | 2000 | 100 |

By forcing Ngoepe to split his practice and game time between two swings, the Pirates stunted the development of his natural right-handed batting.

Switch-Hitting Splits

Before we continue, a quick reminder: a switch-hitter always bats right-handed when facing lefty pitching, and always bats left-handed when facing righty pitching.

Turning a right-handed hitter into a switch-hitter is only valuable if:

1. His platoon split between lefty and righty pitching is smaller than the average split for a right-handed batter, and

2. The resulting overall numbers are better than what he would have hit had he batted right-handed full-time, which would have allowed him to focus all his practice on his right-handed batting.

Tackling No. 2 is possible4, but would be very time consuming and is probably above my pay grade. As a result, the rest of this article comes with the important caveat that we don’t know how Ngoepe would have developed as a full-time right-handed batter. Keep this in mind when considering my analysis of whether switch-hitting benefited him.

No. 1 is easier to figure out: All we have to do is compare Ngoepe’s switch-hitting splits with the normal splits of a right-handed batter.

From 2011-13, the average major league right-handed batters’ OPS was 51 points higher when facing lefties than when facing righties, according to Matt Eddy of Baseball America. Dan Fox of Baseball Prospectus found a similar 52-point OPS split using data from 1970-92. We’ll use Eddy’s more contemporary data, which includes individuals splits for on-base and slugging percentages.

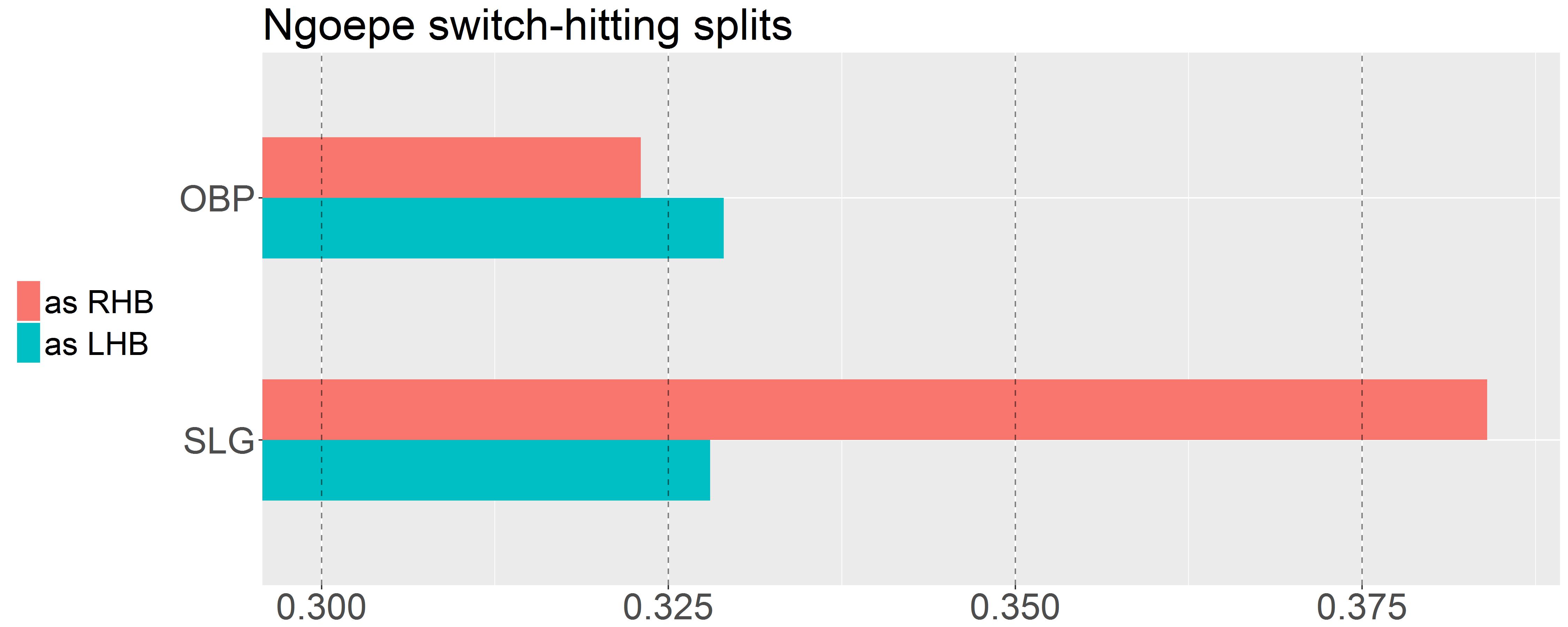

First let’s get a quick visual cue of his splits.

His on-base split is surprising: He actually got on base more while batting from his weak left-handed side, the opposite of what we’d expect (this is what is called a “reverse split”). On the other hand, he’s got a large slugging split in favor of his strong right-handed side, which is normal.

Let’s dig into the numbers a bit more. The table below shows Ngoepe’s stats from each side of the plate, his splits, and the average splits for major league right-handed hitters.

| Split | OPS | OBP | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|

| as RHB | .707 | .323 | .384 |

| as LHB | .657 | .329 | .328 |

| ♦ Ngoepe split | .050 | -.006 | .056 |

| ♦ Avg. RHB split | .051 | .021 | .030 |

Quick and dirty summary: His OPS split is the same as the average MLB right-hander, his on-base split is much lower, and his slugging split is much higher.

We can make our analysis easier by applying the typical right-handed hitter split to Ngoepe’s stats as a left-handed hitter facing righty pitching. The result will be a projection of how he would have fared as a right-handed hitter against right-handed pitching, which we can compare with his actual numbers as a left-handed hitter.

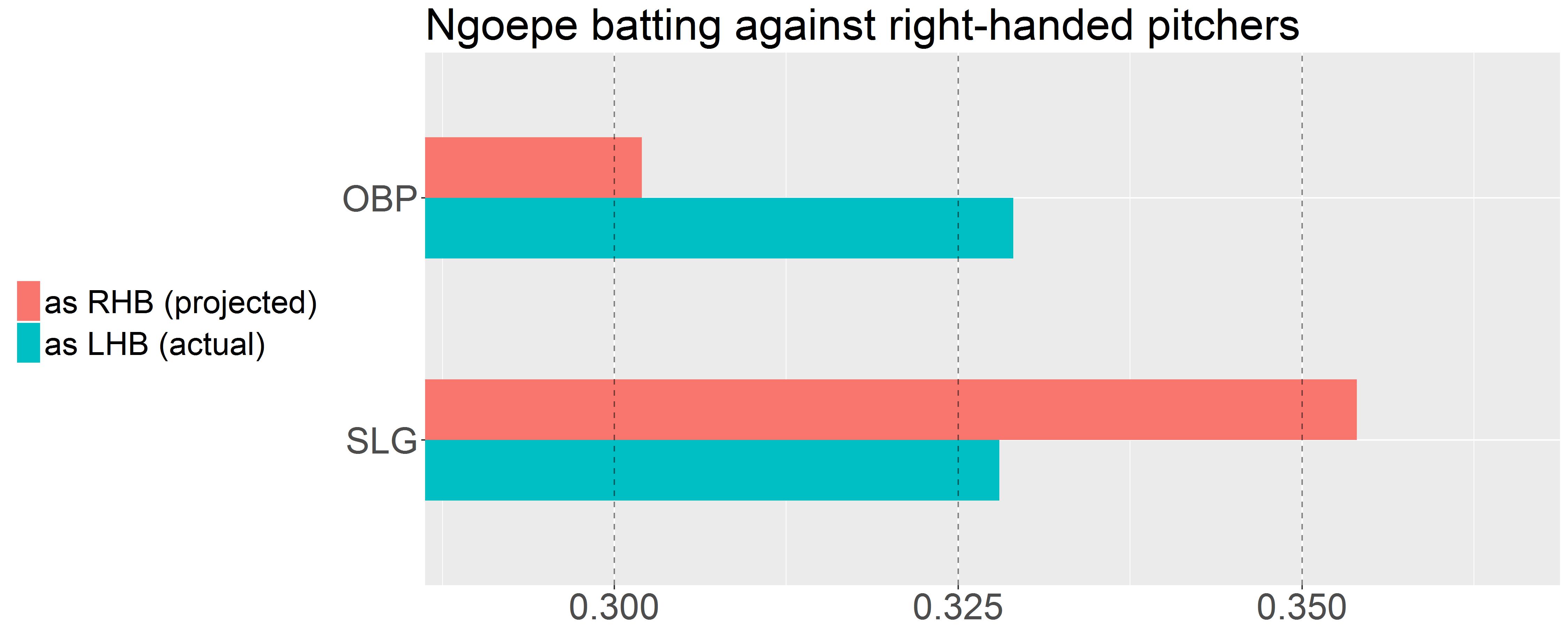

First, a quick visual of the projections.

Quick and dirty: Ngoepe would have hit for more power as a right-handed batter, but would’ve gotten on-base less. Let’s look at a more detailed breakdown.

| Split | OPS | OBP | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|

| as RHB vs RHP (projected) | .656 | .302 | .354 |

| as LHB vs RHP (actual) | .657 | .329 | .328 |

| ♦ Projected full-time RHB benefit | -.001 | -.027 | .026 |

These results offer a mixed picture of whether switch-hitting was good for Ngoepe.

His OPS split is the same as the expected split. If this was the end-all be-all stat, we could declare switch-hitting a failure: Had he batted full-time right-handed, his numbers against righties would be no worse, and his overall numbers would certainly improve thanks to dedicating all his practice to his right-handed swing.

The results get murkier when you isolate each component of OPS.

The projection says that Ngoepe’s on-base against righty pitchers would drop by 27 points had he batted right-handed. That’s a significant amount, and an argument that switch-hitting helped.

The slugging numbers swing the argument back towards the anti-switch-hitting school of thinking: He would have added 26 points batting right-handed.

Weighing OPS

OPS is not an ideal measurement of offensive ability because it weighs on-base and slugging equally. In reality, a single point of OBP has a higher correlation with run scoring than a single point of SLG.

To account for this, I’m going to create a stat called weighted OPS, or wOPS for short.5 According to Fangraphs, a point of on-base is worth 1.8 times more than a point of slugging. The equation for this new stat will be:

wOPS = OBP*1.8 + SLG

Let’s plug these numbers in to get a picture of what Ngoepe’s wOPS would have been batting right-handed against righty pitching compared to his numbers as a switch-hitter.

| Split | wOPS |

|---|---|

| as RHB vs RHP (projected) | .898 |

| as LHB vs RHP (actual) | .920 |

| ♦ full-time RHB outcome | -.023 |

Looking at these numbers in isolation, switch-hitting was good for Ngoepe’s batting against right-handed pitching.

This conclusion is far from definitive. How much would his right-handed numbers have benefited from dedicating all his practice time to perfecting one swing, as opposed to splitting his time between two? It’s certain they would be better — to what degree, I can’t say.

So far, we’ve only looked at Ngoepe’s career stats as a switch-hitter. In Part 2, we’ll break down his numbers season-by-season to see how he developed as a hitter from each side of the plate. Come back next week to check it out.

Footnotes

1 Speed notes

Ngoepe’s speed has been noted by reporters dating back to a 2009 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette piece.

A theoretical benefit of turning a fast right-handed batter into a switch-hitter is he’ll be quicker out of the box when hitting left-handed, and thus increase his number of infield hits.

Despite his speed, Ngoepe has failed to turn into a base stealing threat. Here’s his career minor league stolen base record:

| Steals | Caught stealings | Success rate |

|---|---|---|

| 88 | 57 | 61% |

61 percent is bad. In 2012, the break-even point for stolen base success rate in the majors was 67 percent, according to Fangraphs, and has likely gone up since then. In other words, if a player gets caught on more than one-third of their attempts, the negative effect of those outs outweigh the benefits of the successful steals.

Put simply, 61 percent doesn’t cut it, and it looks like the Pirates have given up on developing this aspect of Ngoepe’s game. In 2015 and 2016 he only had 19 steal attempts. He was caught 10 times.

His speed still gives him value as a pinch runner, but it would be nice if he had base stealing in his repertoire as well.↩

2 Ditching switch-hitting

Ngoepe further explained his decision to give up switch-hitting in a Bucs Dugout article from May 2015.

“The Pirates wanted me to be a leadoff hitter and to wear out the pitcher. I’ve struggled in that department. Left-handed especially, I wasn’t very comfortable hitting to the opposite field … I’m going to stay right-handed because I feel more comfortable …” ↩

3 Fielding notes

If baseball had a designated fielder position, Ngoepe would have made the majors many years ago.

In 2012, he was named the best defensive infielder in the Pirates farm system, and as early as 2014 Pirates Prospects writer Jon Dreker declared that his defense “is already Major League ready.”↩

4 Projecting Ngoepe’s offensive numbers

Here’s the most logical way to project Ngoepe’s offensive numbers had he batted right-handed full-time.

First, get Ngoepe’s right-handed batting vs. lefty pitching stats from his first three minor league seasons (2009-11):

| Age | Level | PA | OBP | SLG | K rate | BB rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | Rookie | 51 | .370 | .385 | 23.5% | 13.7% |

| 20 | A- | 77 | .387 | .444 | 22.1 | 13.0 |

| 21 | A | 21 | .500 | .882 | 23.8 | 14.3 |

| ♦ 19-21 | Rk, A-, A | 149 | .397 | .487 | 22.8 | 13.4 |

Then, get a matching set of right-handed hitters (same age, position, etc.) who have similar stats for their first three minor league seasons and see how their careers progressed. The average of that matching set would be your projection for how Ngoepe would have ended up batting as a full-time righty.↩

5 Other weighted stats

wOBA and OPS+ are more sophisticated versions of wOPS.

wOBA assigns values to every offensive event (walk, single, double, etc.) in proportion to its impact on run scoring. OPS+ takes a player’s OPS and makes adjustments based on his ballpark and the run scoring environment of his league (NL or AL) for that particular season.

Both are adjusted to different scales to make them easier to interpret: the average wOBA is scaled to the league’s average OBP, while the league average OPS+ always equals 100. To clarify, if the league-wide average on-base pct. is .330, then an average player would have a wOBA of .330 and an OPS+ of 100.

wOBA, OPS+ and wOPS all measure the same thing: a player’s total offensive contribution. wOBA is probably the best stat given its precise weights for each possible offensive event.

OPS+ has the advantage of adjusting for park effects — which, unless a park heavily favors either lefties or righties, wouldn’t be relevant for an individual player’s platoon splits — but suffers from not adjusting for the different relative values of on-base and slugging, which wOPS does. Maybe, one day, Baseball Reference will combine the two and create a wOPS+ stat.↩